“Judge Is What I Do, John Is Who I Am”

In the courtroom, Judge John Romero works to be a positive, compassionate force in the lives of families across New Mexico.

The Calling

Sitting in the lunchroom of a retail store, a young man watches President Nixon resign on live television. The Watergate scandal is unraveling, it is fall of 1974.

This young man had already taken the LSAT, but, he thinks to himself: “Wow, all my Dad said about attorneys being crooked, you know, seems to be true, who wants to be one of those scummy guys?”

The man is John Julio Romero, District Court Judge in Children’s Court in Albuquerque, New Mexico since 2003. Romero is a husband, a father, and a grandfather. Romero’s middle name comes from his father, Julio, born on the 4th of July.

“Judge is what I do, John is who I am,” he said, inside his office at Children’s Court.

“What does it mean to be informed or aware or responsive in a trauma-responsive way so that you don’t cause any other harm? You can’t do that if you’re full of yourself and egotistical and think you’re somebody great because you wear a black dress.”

Romero was first recommended to go to law school when he was in the Navy, stationed in the Philippines in the 70s. He was assigned an investigation, which is called a Judge Advocate General (JAG) investigation in the Navy. After the successful completion of his report, his company legal officer suggested he think about law school.

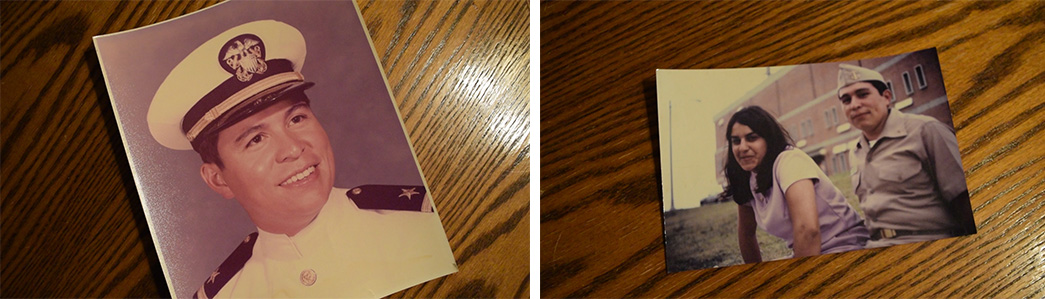

John Romero, and his wife, Amy Romero, while he was in the Navy, stationed in the Philippines.

Romero’s new bride, Amy, agreed. After coming back to the U.S., he passed the LSAT, but first, received a graduate degree from UNM’s Public Administration Program. Simultaneously, he earned his Federal Aviation Administration Journeyman Controller certification.

Six years later, in 1981, he went on strike alongside 12,000 air traffic controllers. Their union was seeking better pay and working conditions. In response, President Ronald Reagan deemed the strike illegal, and after 48 hours, terminated their jobs. Romero was fired.

During this transitional period, the calling to law presents itself in his life again. His pastor at the time was finishing his own juris doctorate, and asked Romero, “well, have you thought of law school?”

Romero takes the LSAT again, passes, and is admitted to the University of New Mexico School of Law. He graduates, and becomes a Family Law attorney. In court, he represented parents in adoption cases, sometimes representing birth parents. He also represented divorcing parents, and he regularly served as the Guardian Ad Litem for children in contested custody cases. Guardians ad litem are lawyers appointed by the court to represent the best interests of the child.

After 18 years of practice in Family Court, a retiring judge suggests that he give some thought to becoming a judge. Romero admits he never had aspirations of becoming a judge.

Amy Romero, at his side, points at him, and said, “you need to think about it.”

Less than a year later, Romero applied for two vacancies that were going to exist at the end of December 2002. He made the short list, but was not appointed that first time by the Governor. A few months later, in spring, Romero applied again for a vacancy, and was appointed to the Children’s Court. This is where he found his calling.

“If we feel called, spiritually, to do what we’re supposed to do, I recognize that I’m not doing this by myself,” said Romero.

The Light

Romero’s courtroom virtues stem from core values that have been carried through the generations of his family.

Romero was born in Embudo, New Mexico, and grew up in La Plata, five miles south of the Colorado-New Mexico border. He grew up alongside ranchers and farmers, raising sheep and cattle. Romero went to a two-room red brick schoolhouse.

As he reminisces, Romero talks about the songs that his father used to listen to, and the life lessons that he gained from his father’s stories. He describes his mother and mother-in-law’s strength. He lovingly looks at his best friend, his wife of 45 years.

Then, Romero focuses on his children. He speaks about his son as strong-willed and independent. The same strength that his mother and mother-in-law commanded, he sees in his own daughter. As he sits in his living room, he smiles when he talks about his granddaughter and his niece; he mentions them as sources of inspiration.

“If we feel called, spiritually, to do what we’re supposed to do, I recognize that I’m not doing this by myself,”

In law school, other students would say to him: “you’re married and you have two kids and a mortgage and a car payment, how can you do this?”

He replied, “the only reason I can do this is because of my family.”

“They are what motivate me, they are what keeps me focused on the reality that there’s light at the other end of the tunnel.”

Romero’s compassion expanded his family. He opened the doors of his own home to be a foster parent. Being merciful and compassionate are essential values that Romero lives by.

“I remember growing up and always going out, helping people we knew and people we didn’t know, and seeing community as family,” Romero’s daughter, Felicia Pugh said.

Icebergs in the Desert

Romero speaks often about the trauma he sees in the courtroom, and how he challenges his colleagues to deeply consider what it means to be trauma-informed.

He works closely with a team social workers, probation officers, attorneys, and public defenders. This team works to ultimately protect the public’s interest, and to do what is best forthe young people in our community.

“Everyone that walks through that front door of our courthouse has some form of trauma in their lives,” Romero said. “Judgements based on what is visible is just looking at the tip of the iceberg, without looking at the other 80 percent.”

Previous Children’s Court Judge, Michael Martinez, gave his advice to Romero, and told him about the iceberg of the Children’s Court: It’s 20 percent bench time and 80 percent community time, because it is impossible to make good, just decisions for your community without understanding the community itself.

“I think about this a lot – he not only looks at the child, he looks at the whole family, he’s got the compassion for the families,” Amy Romero said about her husband.

“Everyone that walks through that front door of our courthouse has some form of trauma in their lives,” Romero said. “Judgements based on what is visible is just looking at the tip of the iceberg, without looking at the other 80 percent.”

Leave a Reply