Planting the Seeds of Change

After a lifetime of nurturing his own liberation, community activist and organizer Arturo Sandoval is helping New Mexican families grow their way out of oppression.

On an evening in 1896, under the cover of the northern New Mexico night, Leonardo Salazar prepared to cut down fences and reclaim land. He was a member of Las Gorras Blancas, a group of land grant defenders, who rode through New Mexico tearing down fences placed by white-Americans for their ranches and ever-expanding railroads.

As he donned his cap, his eight-year-old daughter, Margarita, watched. Leonardo told her she must not tell anyone what he was doing for fear he would be killed. But, Margarita did tell.

She repeated the story to her grandson, Arturo Sandoval, in 1972 as he prepared to go to trial for refusing induction into the Vietnam War.

“It was her way of telling me, ‘you’re a part of something bigger,’” Sandoval said.

This bigger plan became Sandoval’s lifelong journey of liberation and justice through community organizing and connecting with the land that raised him.

Sandoval, 69, continued to organize for social justice in New Mexico throughout his college years with the United Mexican American Students (UMAS). Sandoval describes UMAS as idealistic and, through direct action, transformative to the university.

“He was very dynamic and a spokesperson for Mexican Americans at that time,” said Dr. Felipe Gonzales, professor of sociology at UNM. Gonzales, Sandoval’s longtime friend, directs the School of Public Administration.

Gonzales met Sandoval in a sociology class in 1968. He describes Sandoval as a natural organizer who often used class discussion time as a catalyst for talk of social change and of ways to improve conditions for poor communities of color in New Mexico.

“[He] had a very strongly developed awareness of issues in relationship to the Chicano and Chicana people,” Gonzales said.

Sandoval’s awareness of oppression and colonization has informed his work to decolonize communities, including helping to organize the first Earth Day in 1970.

“The physical environment is as important as the spiritual and political environment,” he said, “I came to Earth Day because I saw how everything was connected.”

Sandoval sees racism, environmental injustice and colonization as interconnected threads. They are the gnarled roots entangling every facet of life in New Mexico; the politics and economics, food and water, the very air we breath.

Throughout his life, Sandoval’s work has addressed the damage from those interconnected issues. After years as a journalist, and continued organizing on behalf of New Mexico’s marginalized communities, he started the Center of Southwest Culture (CSC).

“I’m starting to really formalize my struggle, so it’s not just me out there. It’s an organization that’s actually evolving and that will be able to continue this work way past my time,” Sandoval said.

A Calling Written in His Roots

Dried leaves crunch beneath Sandoval’s feet as he walks the short rows of dormant peach trees and dusty soil mounds of Albuquerque’s Hubbell House. Built in the 1860s, it is the site of just one in a series of Sandoval’s co-ops that sprout in the fertile patches of the Rio Grande Basin.

“There’s such a deep connection to land here,” Sandoval said as he walked through the Hubbell House gardens and chatted with the groundskeeper.

Sandoval builds these co-ops through CSC, which he helped found in 1991. The center has an economic development division called the Cooperative Development Center that assists Indigenous, Mexicano and Chicano families in starting and maintaining businesses in organic farming, cultural tourism and more.

“He wants to be able to go back to the times where people were self-sustaining,” Gonzales said, “He feels that that is really the way to go if there’s going to be any real success in bringing the people out of conditions of low incomes and poverty.”

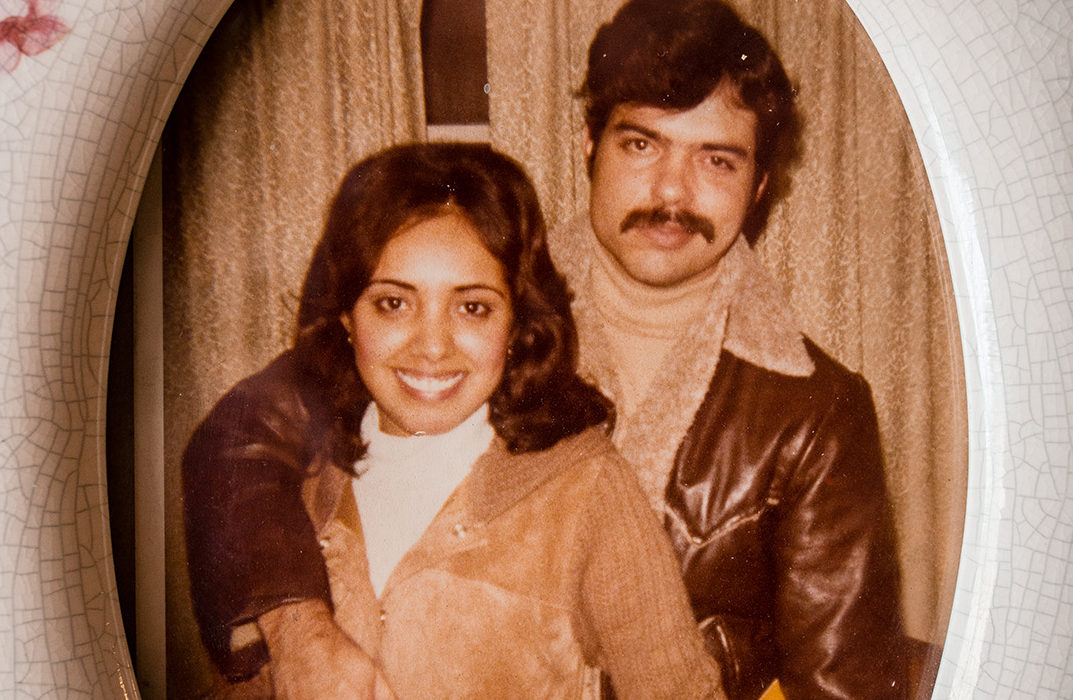

Building these co-ops is the latest project in a lifetime of social justice work. Sandoval considers himself predestined by his grandparents and his mother, Anna Kavanaugh Sandoval. Anna, Sandoval says,became a sounding board for the abused women in her community.

“I think she always felt like she never had access to justice in her own life, so it was a real hunger in her to see it in others,” Sandoval said.

“I think she always felt like she never had access

to justice in her own life, so it was a real hunger

in her to see it in others,”

Passing the Baton

Oriana sits at her desk and waves her hands to fan away tears as she talks about her father and the work he has done for New Mexico.

“I feel really blessed to have parents, and my dad in particular, who really has that sense of community and justice,” Oriana said.

Oriana has found her own path into social justice work as the director of the New Mexico Center for Civic Policy, an organization that advocates for underrepresented communities’ involvement in policy making.

“My father is the great organizer and policy thinker, for sure,” she said, “but his gift is being able to be on the ground and motivate people.”

While Sandoval might have a gift for working with people, he still sees real barriers to creating change that go deeper than motivating.

“I can get people out farming, but the hard part is how do I bring them around to seeing the world differently? To be critical thinkers—-that’s the hardest thing,” Sandoval said.

Sandoval can spend years with a family developing a co-op. He says that budding organizers would be wise not to expect immediate change, but rather, to look at their work as being part of a long-term goal for a better society.

“This is not a short term gig,” he said, “this is a lifelong calling.”

If social change requires a lifetime of work, Oriana sees her father as having what it takes to get it done.

“[He’s] tenacious…he accomplishes what he sets out to [do],” she said, “It may take a year, it may take 20 years, it may take 30 years, but it’ll come to fruition.”

Sandoval stands with his arms crossed and surveys the Hubbell House grounds in front of him with a grin on his face. He is planning more co-ops in the hopes of reaching Mexico in 2017 and of putting them to work for families who long ago secured the rights to the land and water.

“I’ve been organizing for 50 years and I feel like I’m just really on the verge of getting good at it,” Sandoval said.

At the moment, 15 of Sandoval’s co-ops are operating around New Mexico.

“I’ve been organizing for 50 years and I feel like

I’m just really on the verge of getting good at it.”

Leave a Reply